“Oftentimes, we have to poke history, like, ‘You are sleeping. What is going on? Wake! Wake up!’” said Victor Ehikhamenor, a Nigerian multidisciplinary artist, to the Guardian.

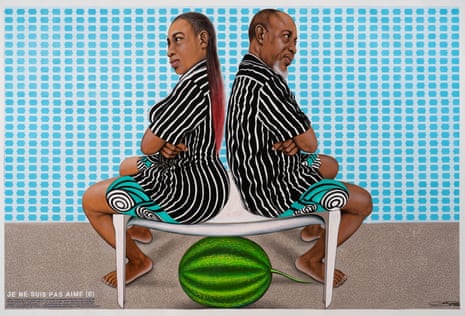

His body of work, which encompasses large-scale tapestries, metalwork and pointillism portraits, is featured in the new exhibition Retro Africa: Do This in Memory of Us, a collaboration between the Nigerian gallery Retro Africa and New York-based gallery Lehmann Maupin that gives the viewer the opportunity to question and possibly reframe history.

“For the longest time, if you look at the history of western art, there’s a lot of representation of great white men, of patriarchy, and all of that, which is a [display] of white masculinity,” Ehikhamenor said. “You go to museums, that is what you see. And you are looking, [asking] ‘Where is my father? Where is my great-grandfather? Where are my ancestors? How are they represented, if not in anthropological photographs that were taken by colonial masters that came? How is our artwork represented in museums?’”

Retro Africa: Do This in Memory of Us features three Black artists, Chéri Samba, Nate Lewis and Ehikhamenor, and is curated by Retro Africa gallery owner Dolly Kola-Balogun. Through the exhibition, Kola-Balogun, a 27-year old UK-born Nigerian gallerist, curator and hotelier, endeavors to remove the voyeuristic lens of Africa and center Africans in the storytelling, shifting from a historically colonial perspective to a contemporary, autonomous one. She sees the exhibition as a conversation, telling the Guardian: “It’s a dialogue between three different black experiences and black people who have different upbringing, different backgrounds, but a common ancestry and a common lineage, some of which is a conversation about historical blackness and our tradition. This is a dialogue amongst black people, within and to black people, and in that dialogue the rest of the world is the audience.”

The exhibition displays the varied field of contemporary African and African-based art, of stories told through metal, oil paint and rosary tapestries with mosaic-like images.

“A lot of the works are very historical but they are also very contemporary,” said Ehikhamenor. For him, art can be an evolution of traditional native references and materials, something he feels gets lost when westerners look at African art. “The way [contemporary African art] is consumed is a little bit different. There’s a certain lens people bring to it, which can be a bit myopic sometimes. I really hope that people commit to it with an open mind,” says Ehikhamenor.

Nate Lewis, the only African American artist in the exhibition, is inspired by patterns and rhythms as well as music. His art invites viewers to “build bridges between the different ways of seeing”, he says. “What we’re doing right now, more than anything, is making this bridge, filling in the space that hasn’t been filled in. Filling in everything we weren’t taught, filling in everything that is hidden, filling in this gap between Africa and American Americans. Filling the gap between the time before the Atlantic slave trade. It’s that connection.

“There are African American classes but we’re not taught African history. To me, it’s a part of completing the story and tapping into the thread and similarities and building bridges amongst us,” Lewis says.

As he suggests, the show bridges the gap between the past and present, between anglophones and francophones, between the told story of Africa and the lives lived by Africans, between the internationally neglected African art scene and America, a place which Kola-Balogun believes can open up the international market for contemporary African art. “[Americans] only understand contemporary African art through the lens of Europeans,” she said. “I think that it would be good to have a direct relationship, a direct presence in the US, and to go where very few people are going. To have an African-owned gallery in the US, curating shows in the United States at the very highest level of the market. That’s not just something I enjoy, that’s my ethos.” In fact, Kola-Balogun hopes to continue to do US-based shows, and to open a Retro Africa in Miami, followed by several more across the world.

Kola-Balogun sees the exhibition and, by extension, Retro Africa, as she sees herself– as a global conduit. She started the gallery as a way to center contemporary African art, remarking, “I had a preconceived idea of what African art was and that’s just largely due to a failure of institutional growth in my region,” she said. “African art, for me, was filtered through the lens of [the] media and the tourism industry, which was primarily just very decorative and in terms of painting, very simplistic. Nothing contemporary.”

Retro Africa, she explains, is a means to stimulate and display the contemporary art scene in Nigeria. “We have very few, if any, museums. Especially, none, at the moment, are contemporary art. I thought that it was a shame that very few of us, with the exception of those who were at the forefront of this a long time, had seen the value of [African] contemporary art. I thought, ‘Well, this is what I want to do with my life. This is the experience I want to give to other people, both abroad and in Nigeria.’”

For Lewis, the exhibition serves as a support to the Black community. “You have to build up your community. You have to believe in your community,” Lewis said. “It’s important that we intentionally try to put our resources, our time and our money in black institutions, in black builders and creators.”

“Art is meant to be seen, said Ehikhamenor. “It’s a way of exposing our interiority. Art is not just art for art’s sake, for the African artist. It’s our way of interpreting history … It’s based on how we represent our ancestors and all of that. It’s important that we begin to show those works. We’re not the ones that started it but we also don’t want to drop the ball. I don’t want my generation to be the one that lowered the standard for my race. We’re carrying a lot of burden on our shoulders but we have people that have helped us to lighten that burden. All we have to do is reference those people. All we have to do is look at what they did. It was heavy for them!”

“There’s been blocks of time of history that haven’t been paid attention to,” Lewis said. The exhibition “is a celebration. It is progress,” said Lewis. Ehikhamenor agrees: “What is special about showing here is that things are changing. Twenty years ago, even 15 years ago, this whole thing of artists of color having opportunities to show in blue-chip galleries and being seen in museums, you can count them on one hand. Now, things are changing and it’s optimistic. That means the world can change.”

Retro Africa: Do This in Memory of Us is showing at the Lehmann Maupin until 17 August